POWER OBJECTS

Joyce J. Scott at the Baltimore Museum of Art

By J Taran Diamond

Joyce J. Scott: Walk a Mile in My Dreams closes July 14, 2024

The 130+ pieces in this Joyce J. Scott retrospective span 50 years, from the 70s to the present

Works on display include jewelry, sculptures, performances and recordings, and garments and textiles

They focus on different facets of Scott’s practice, including heritage and ancestry, relationships to the body, and racial and sexual violence and related injustices around the world

Joyce J. Scott: Walk a Mile in My Dreams

March 24–July 14, 2024

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD, US

To be a contemporary jeweler in Baltimore is to be in the orbit of Joyce J. Scott. You hear from colleagues and friends about her larger-than-life personality, presence, and practice. This extraordinary quality is strikingly apparent in Walk a Mile in My Dreams, a retrospective of Scott’s work spanning from the 1970s to the present. The exhibition features more than 130 works from more than 70 private collections and museums. Works on display include jewelry, sculptures, performances and recordings, and garments and textiles.

The scale of Scott’s practice over half a century is so massive that a single exhibition, even one as large as this, cannot contain it. The exhibition is divided into 10 thematic sections, each characterized by its own conceptual frameworks and goals. Therefore, it is better understood and viewed as a series of smaller exhibitions. The sections are deeply interconnected, but focus on different facets of Scott’s practice, including heritage and ancestry, relationships to the body, and racial and sexual violence and related injustices around the world.

Upon entering the exhibition, one is met by the first of the retrospective’s sections, The Threads That Unite My Seat to Knowledge (2024). The environment, constructed as a site for Scott’s performances, toes the line between space, sculpture, and an assembly of distinct objects. This work was commissioned specifically for the exhibition. With it, Scott succeeds where many sculptors fail: the work is massive but is not characterized solely by its largeness. Rather than explicitly asserting itself as a monument, this work is evocative of a domestic space, familiar in purpose if not quite like a typical room in a home. Quilts and beaded figures gaze down on the viewer from overhead. It feels almost as though the viewer is a child and an older relative is about to tell a story. Even when Scott is not activating the environment through performance, this sculpture sets the scene for what is to come.

In addition to Scott’s work, this portion of the retrospective features quilts by her mother, Elizabeth Talford Scott, and other members of Joyce J. Scott’s family. Elizabeth Talford Scott’s work was recently the focus of another exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art. It is only fitting that the retrospective would open with a space for intergenerational storytelling. Held in the city where Scott was born, this retrospective of five decades of artmaking serves as a homecoming and tells a story.

The Threads That Unite My Seat to Knowledge is followed by “Fashioning Consciousness.” This section primarily focuses on garments, jewelry, and sculptures made in the 1970s and 1980s. It highlights the time Scott spent traveling and engaging with cultures all over the world, and the impact of those cultures on her practice. The garments are as spectacular and intricate as one might expect from Scott, as are the numerous sculptures and pieces of jewelry. As impressive as the garments are, two necklaces truly shine in this section. The first is Joyce’s Necklace (ca. 1978–1985). It features a variety of collected beads and charms. Though stylistically somewhat different from her more recent jewelry, it is nonetheless unmistakably Scott’s work. The necklace serves as a journal of Scott’s travels and experiences, documenting those experiences on the body in the same way stamps would document them in a passport.

The second necklace is We Two (ca. 1970s), a collaboration between Scott and the late Art Smith. This piece is more visually understated than is typical of Scott’s jewelry, due to the iconic form of Smith’s Half and Halfnecklace, which serves as the substrate for Scott’s beadwork. But it, too, is unmistakably hers. The necklace is beautiful, but it stands out as exceptional for reasons beyond its beauty. We Two links the practices and narratives of present-day Black jewelry artists to Smith, a leading figure in 20th-century modernist jewelry.

Other sections of the exhibition focus on more politically pointed aspects of Scott’s practice in a few different ways. Messing with Stereotypes uses humor to confront racism and anti-Black stereotypes. Through this humor, Scott simultaneously confronts issues directly and disarms or ridicules those who perpetuate racist cultural or sexual narratives. This confrontation through humor is seen in the Still Funny series, in which Scott beads interventions on found ceramic figurines. These objects mock stereotypes about the sexual anatomy and appetites of Black people, as well as the fetishization of interracial sex.

The section “Bearing Witness” confronts racial violence in a much more somber tone. It focuses on lynching and police brutality as real threats in the United States. The beaded sculptures and jewelry in this section take advantage of the allure and materiality of intricate beaded forms to demand viewers’ attention for often-uncomfortable topics. Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon (1991) is a direct response to the incident its title references. It renders the grotesque violence of police brutality against King in twinkling black glass. Lynching Necklace (1998) depicts similar violence against an unidentified victim. This necklace is notably the only piece of jewelry in the retrospective accompanied by a photograph of the object on a model, Scott herself. The presence of this photograph alongside the work places the depiction of graphic violence directly against the backdrop of Black bodies, emphasizing the acts depicted in these artworks as real and legitimate threats faced by Black people.

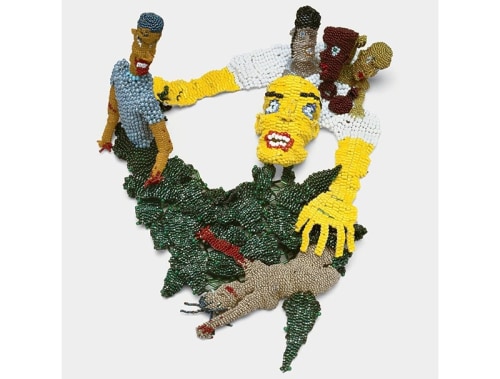

The adjoining section, “Better Out Than In,” places an emphasis on rebirth and renewal from this violence. It centers on Lynched Tree (2011/2024), a large sculpture composed of a beaded figure hung by its ankles and a collection of found and made objects. This arrangement is recognizably a depiction of violence, but is also suggestive of childbirth, as objects seem to spill forth from between the figure’s legs.

The exhibition closes on “Solace for a World in Constant Flux.” This section features a selection of eight figurative beaded sculptures, described as power objects. The figures are largely modeled after deities or protector figures from throughout Scott’s career. They are arranged on an elliptical pedestal that occupies an entire room in the museum. The brightly colored sculptures appear as a pantheon to guide their maker, or perhaps their audience. These works demonstrate a quality that makes Scott’s work so compelling: In its spectacular intricacy, her beadwork exerts an arresting, even transfixing, power over viewers. That power is present even in the absence of explicit political imagery.The tiny beads that comprise Scott’s work form bodies almost like the cells in our own bodies. They interact both literally and metaphorically with ours, before sending us back into the world outside the gallery walls.