It's All Political

By Susan Tallman

Two thousand seventeen, in its final throes, was dubbed the Year of Women, acknowledging a stretch of activism that began with the Women’s March on Washington in January and ran through December with #MeToo. There are a few problems with this appellation: first, fobbing off half the population with a 365-day patch seems to leave the millennia to either side in the default position of patriarchy; second, women didn’t suddenly become politicized in 2017 (please see history of civilization); and third, women were hardly the only people to become politicized in this particular 12-month stretch.

In 2017 everything became political. The contemporary art world is no stranger to grandstanding political gestures, but as was made clear at New York Print Week in October, political content now suffuses every venue, contemporary and historical, topical and abstract.

One of the most sobering displays of Print Week was at the Satellite Fair, where M. Lee Stone Fine Prints hung a wall with anti-lynching prints produced in the mid-20th century by artists such as Elizabeth Catlett, John Steuart Curry and Louis Lozowick, as well as lesser-known figures. Though visual style may have changed over the past 80 years, the subject matter of grieving mothers and angry white men, guns in hand, feels horrifically current.

Among artists and publishers producing new editions, the gloves are now off. Images addressing specific policies, events and political persons have moved from the periphery to the center of art production, while the work of artists long concerned with injustice and inequality now lands a more visceral punch.

At the usually staid IFPDA Fine Print Fair, Two Palms Press showcased Downtown 4 Democracy (D4D) editions, whose sales support strategic political actions such as the Democratic effort to retake Congress. The editions range from the allegorical (Cecily Brown’s lithe redrawing of Pieter Breughel’s 1559 Battle Between Carnival and Lent), to the wittily referential (Jonathan Horowitz’s golden update of Jasper Johns’s 1969 Moratorium poster), to the literal (Marilyn Minter’s hydrocal Trump Plaque, which simply presents the predator-in-chief’s name and face above his own words).

Inaugurating a new protest poster project at the fair, Durham Press distributed 200 screenprints by Chitra Ganesh in which crows and hands of many colors assemble the message “RISE UP / RESIST.” Offered on a pay-what-you-can basis, the prints raised $1,300 for the Center for Popular Democracy’s hurricane relief efforts in Puerto Rico. At the INK Miami Fair in December, the screenprinted poster was a vibrantly colored target by Polly Apfelbaum with “ME TOO” emblazoned in the center, which raised $2,000 for the gender justice organization, the Third Wave Fund. (Durham plans to continue this effort, though some works may be in limited editions with set prices.)

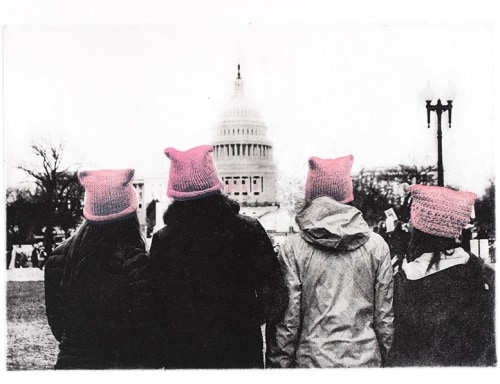

The Women’s March lives on in multiple projects, including Soledad Salamé’s hand-colored solar etching after photographs taken at the march, on view at Goya Contemporary, the first of which shows four women in pink “pussy hats” gazing at the Capitol. At the E/AB Fair, Planthouse drew an enthusiastic response to Say a Little Prayer for U.S., a set of screenprinted linen prayer flags by the Victory Garden collective (Louise Eastment, Jess Frost, Tara Geer, Wendy Small, Janis Stemmermann and Katie Michel). The linen flags are a more permanent distillation of the hundreds of paper flags contributed by artists to a summer exhibition of the same name—both are meant to continue the momentum of the march, and bear messages ranging from “Save the EPA” to a mute portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

The complexities of racial and cultural identity were investigated and articulated in numerous projects, ranging from Fred Wilson’s enigmatic nod to Alexander Pushkin, Queen of Spades (2016) at Eminence Grise Editions to Kara Walker’s magisterial etching triptych Resurrection Story with Patrons (2017), printed and published by Burnet Editions. Walker’s print augments her familiar antebellum shadow drama with a strong smack of Christian iconography: its central section—in which Lilliputian figures use ropes to pull upright a black female torso—is flanked by panels in the manner of an altarpiece with donor portraits to either side. The silhouetted “donors” are black in physiognomy but white in color, and their attire suggests the 18th century. The three parts are unified by long diagonal boards that shift in character from scene to scene—architectural beams, the shattered ribs of a ship, a carried cross. The precariousness of hope, rather than the stability of despair, seems the critical subject here.

The plights of migrants and refugees was a recurring subject, both hopeful and heartbreaking. In Ramiro Rodriguez’s woodcut La Que Bebe No Vuelve (2016, Segura Art Studio) pictures a story the artist’s grandmother told of crossing the Rio Grande as a child: she had heard that those who drink the water never returned to Mexico—she drank, while her sister abstained, but both remained in the States. The magical small etchings of José Antonio Suarez Londoño (shown by Harlan and Weaver) are always elliptical and complex—spaces littered with figures and diagrams and animals and elegant webs of line. Thus the boat shapes, silhouetted fish and human body parts in his etching No. 294 (2016) might seem simply dreamlike, were it not for the subtitle, Lampedusa—the Mediterranean island between Libya and Sicily off of which thousands of refugees have drowned trying to reach Europe. Even dreams cannot escape the political wreckage.

This small print—a work by a Latin American artist about a crisis connecting North Africa and Europe—is a reminder that despite the American habit of sucking all the air out of the room (and all the attention out of the media), the current unraveling of political and ethical norms is a global phenomenon. The Crying Game (2015–2017), a suite of 30 etchings by the Dutch-British artist Marcelle Hanselaar, released concurrent with Print Week, is a broad survey of villainy and victimization: rape, mutilation, sexual slavery, chemical warfare, acid attacks, torture in many flavors. Hanselaar acknowledges her debt to Goya and Dix as models of both powerful narrative summary and incendiary outrage. Unlike them, she has not experienced war firsthand, but her most affecting images are of street fights, screaming couples and junkies—neighborhood tragedies we may walk by on any given day.

Gemini at Joni Weyl’s Ann Hamilton exhibition featured three bodies of work: large, luxurious photoscreenprints of zoological specimens from a natural history museum, a series of book end-pages collaged with fabric and snippets of text, and sheets that from a distance appear as elongated clouds of color. Closer up, it is clear that these clouds are composed of blind-stamped words. The nearly seven-foot-tall RIGHTS and the smaller EQUAL AND INALIENABLE RIGHTS OF ALL both employ the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, established by the fledgling United Nations in 1948. (Despite legal challenges from, among others, the United States of America, the UDHR remains the de facto international standard against which the protection and violation of human rights are measured.) The artist created a concordance—a form of indexing, usually reserved for scripture, in which individual words are identified and grouped, but presented within their original verbal context. She then arranged the concordance such that the indexed words are stacked in a vertical spine that spells out sections of the declaration’s opening statement: “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…”

A third print, THE ANIMAL HAND, applies the concordance technique to Aristotle’s On the Soul, and forms a bridge between the UDHR pieces and animal screenprints produced at the same time. The book-page collages—one of which bears the single word “idealism” above a textile swatch—similarly bridge the physical and the conceptual. In another year, this grouping might have been understood as a prompt to consider the ontology of being human, the glory and tragedy of the human compulsion for knowledge and control. But in 2017, in America, the hanging of these fragile, hopeful texts alongside eyeless birds and long-dead bush babies appeared to be a statement of clear and present danger.

William Kentridge once observed, “I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain things. An art (and a politics) in which my optimism is kept in check and my nihilism at bay.” Keeping optimism in check is no longer our problem, but the battle against nihilism needs all hands on deck.

In this context even small gestures can be powerful, such as Jaume Plensa’s simple letterpress print, done with Bleu Acier. Like a Victorian wood engraving showing how to make shadow puppets, the image shows a pair of silhouetted hands whose extended fingers somehow cast a shadow spelling out the word WE. The print summarizes Plensa’s perennial concerns as a sculptor—community, connectedness, transparency, the intersections of individual bodies and shared language—but in 2017 it was hard not to also read it as a truncated echo of “YES WE CAN.”