Women Take the Spotlight in a Pair of Art Shows at the A.U. Museum. ‘Positive Fragmentation’ and ‘Fields and Formations’ Showcase Female Artists from the Mid-Atlantic and Beyond

By Mark Jenkins

The American University Museum exhibition “Positive Fragmentation: From the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation” is characterized by splintered imagery and ruptured identity. But that doesn’t mean the artwork itself is chopped into little pieces. In fact, “Positive Fragmentation” is one of two A.U. Museum shows — both highlighting art by women — that include pieces on an epic scale.

The art in “Fragmentation,” which was organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts (closed for renovation), consists of prints and collages. Some of the 21 artists use found images and printmaking techniques to amass repeated or related images into larger works.

Thus Christiane Baumgartner’s minimalist yet imposing “Stairway to Heaven” fills a large wall with five woodcuts modeled on photos of video static, but suggesting landscapes; they’re staggered so that what appear to be horizons align across all of them. Similarly, Sarah Morris’s “Dulles,” inspired by that airport’s sleek design, is a set of nine framed prints whose blocks of clean, bright color flow into one other.

Jennifer Bartlett also plays with architectural form with screen prints of colorful grids that each incorporate the basic shape of a house. Less rectangular, but still evoking buildings, are Nicola Lopez’s multilevel collages of architectural and industrial details in swirling arrangements.

Another large grouping of variations on a theme is a set of images, utilizing a wide range of printmaking techniques, by Ellen Gallagher, who culls her source material from advertisements in magazines published for Black consumers in the mid-20th-century. The artist transforms the pitches for hair and cosmetic products (including skin-lightening potions) and get-rich-quick schemes by adding text, glitter, gold leaf and Plasticine forms. Nearby is another commentary on minority culture and partial assimilation: a lithograph by Wendy Red Star that incorporates photos of automobiles — decorated for the Crow Fair, an annual gathering for Great Plains tribes — and a border of traditional Indian decorative motifs.

Among the artists who focus on the body are two of the show’s best-known artists — Louise Bourgeois, who died in 2010. and Judy Chicago — as well as Wangechi Mutu. Chicago’s symbolic renderings of female genitalia are sleek and cleanly designed, suggesting less human flesh than the machine-tooled plastic abstractions of her early career. Mutu, however, evokes physical frailty with prints of faces superimposed on 19th-century medical illustrations of uterine tumors.

A different sort of vulnerability is the subject of “Thalassa,” a depiction of the ancient Greek sea spirit made in reaction to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill by Caledonia Curry, who works under the name Swoon. This silk-screen print of a woman surrounded by aquatic creatures was mounted on a battered white wooden door to give it a sense of damage and fragility. But the piece, like so many in “Positive Fragmentation,” also demonstrates a bold ambition to push works on paper into unprecedented sizes, shapes and formats.

The second show, “Fields and Formations: A Survey of Mid-Atlantic Abstraction,” is a version of one that previously ran at the Delaware Contemporary, a Wilmington art space. It presents work by 12 female and nonbinary artists from the Mid-Atlantic region, several of whom will be familiar to regular D.C. gallery visitors.

These include the two whose contributions are the most physically overwhelming: Jae Ko, a Washington area sculptor, and Linling Lu, a Baltimorean who shows frequently at D.C.'s Hemphill Artworks. Ko’s “Flow” is a massive wavelike form made of stacked, rolled white paper. It crests, quietly yet formidably, across from Lu’s “Eye of Wisdom,” which arrays 10 large circular color-field paintings around an even larger one. Lu’s immaculately handmade pictures, which consist entirely of brightly hued concentric circles, appear simultaneously gamesome and cerebral.

“Fields and Formations” is on the museum’s third floor, which has a high-ceiling gallery (hosting Ko and Lu’s pieces) and a lower-ceiling one. Most of the other D.C. artists, including some known for working big, are in the latter. The room holds modestly scaled artworks by Carol Brown Goldberg, including two glistening paintings whose boundaries are marked by fields of silvery dots; and Linn Meyers, who’s showing intricately oscillating drawings on graph paper and book pages from which all but a few words have been cut away. Slightly larger are two handsome abstractions by painter Maggie Michael, notably one painted in watery blues, blacks and earth tones.

The Philadelphia artists are Natessa Amin, who draws on such diverse decorative traditions as Indian, African and Pennsylvania Dutch; Jesse Harrod, a fiber artist whose 3D wall pieces are in graduated color and undulating forms; Arden Bendler Browning, whose energetic paintings are free-form yet meticulous; and Alexis Granwell, who highlights white papier-mâche sculptures with touches of color.

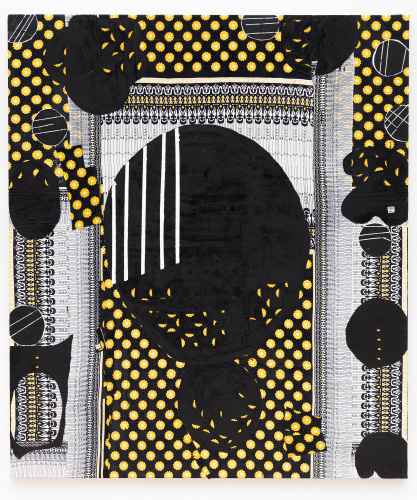

The rest of the Baltimore contingent consists of Jo Smail, whose patterned abstractions incorporate African fabrics; Alex Ebstein, who makes sculptural paintings from such materials as cutup yoga mats; and Maren Hassinger, whose circular nest of twisted newspaper fragments makes such a tidy — make that messy — contrast to Lu’s style of painting that the two are juxtaposed on the cover of the show’s catalogue. Between Hassinger’s clumped assemblage and Lu’s pristine orbits lies a whole region of contemporary abstraction.